ʻAlala Recovery

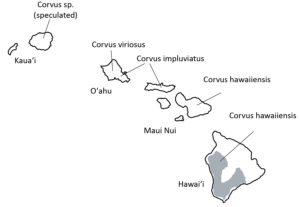

RESTORING HAWAIʻIʻS NATIVE CROW TO THE WILDʻAlalā (Hawaiian Crow; Corvus hawaiiensis) is the last endemic Corvid species found in Hawaii. The last wild birds were seen in the South Kona district of Hawaiʻi Island in 2002. Fossil evidence shows that Corvus hawaiiensis, or a very similar subspecies, was found on Maui and Hawaiʻi Islands. Their documented range on Hawaiʻi Island covered forest habitats from 1,000 feet in elevation to about 8,200 feet in elevation. ʻAlalā were known to exist throughout their historic range on Hawaiʻi Island from the 1800ʻs, but the wild population started to decrease dramatically. By 1976 there were only 76 individuals, by 1992 there were only 13, and in 2002 the last pair of birds were seen in the wild.

Like many other native forest bird species, ʻalalā are primarily threatened by non-native species, loss and/or alteration of habitat, and introduced diseases. Wide-scale deforestation for agriculture and livestock grazing has reduced the amount of forest cover on the islands to a fraction of prehistoric levels. The subsequent addition of invasive plant and animal species further eroded the extent of native forest and reduced forest quality throughout the island. Furthermore, introduced avian diseases such as avian pox, avian malaria, and toxoplasmosis effect ʻalalā. Non-native vectors such as mosquitoes and free-ranging cats spread these diseases.

Species Status

Extinct in the wild. ʻAlalā are the sole surviving member of 5 endemic corvid species once found on at least four of the main Hawaiian Islands. Fossil evidence shows ʻalalā, or a similar subspecies, to have been found on Maui and Hawaiʻi Islands. The last wild individuals were found within the South Kona district of Hawaiʻi Island.

Conservation Breeding

Reintroduction

Reintroduction efforts began in 2016 with the release of birds into the Puʻu Makaʻala Natural Area Reserve on Hawaiʻi Island. Releases continued through 2019. A total of 29 birds were released in Puʻu Makaʻala Natural Area Reserve. With increased mortalities, release efforts were paused and the remaining 5 birds were recaptured and returned to the conservation breeding program. The partners of The ʻAlalā Project are working towards the next steps in the reintroduction process. Reintroduction efforts have been proposed to shift to releasing birds within Maui Nui. Read the draft Environmental Assessment for the proposed release of ʻalalā on Maui here.

Save the Forest, Save the Birds

It takes a community of dedicated individuals and support to make conservation happen